[The cover to Batman: Death by Design]

[The cover to Batman: Death by Design]

What if Bruce Wayne wanted to demolish Penn Station in order to surreptitiously construct an auxiliary Batcave beneath the new building? That, in essence, is the plot of Chip Kidd’s new graphic novel Batman: Death by Design. Though a few familiar faces –and grins– make an appearance, Death by Design is, for better and worse, a comic book about architectural preservation and the construction industry.

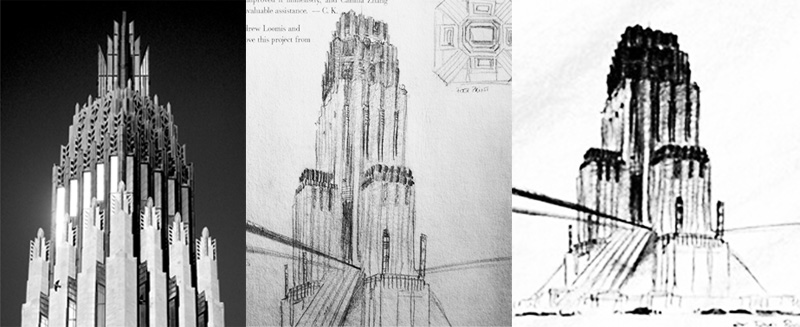

[left: Boston Avenue Methodist Church; center & right: sketches of Wayne Central]

[left: Boston Avenue Methodist Church; center & right: sketches of Wayne Central]

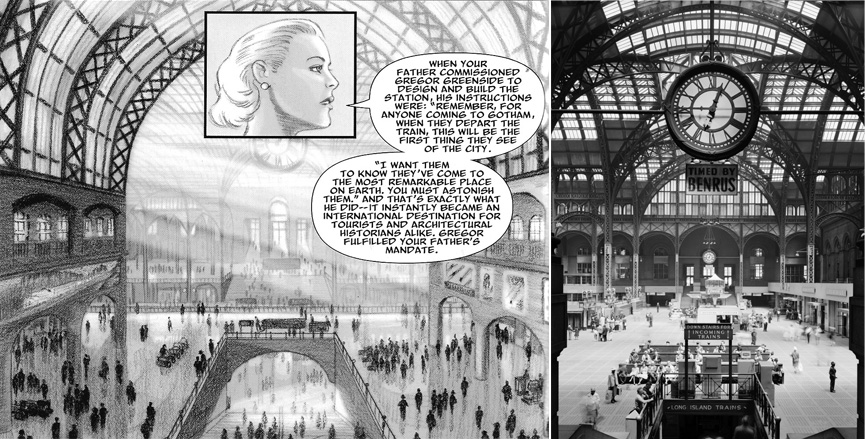

Of course, there is no Penn Station in Gotham City. Instead, a thinly-veiled proxy is presented in the form of Wayne Central Station. Every action, every conflict, and every single character in this story is motivated by the desire to either preserve or demolish this building, which is part high rise, part train station, and part Tower of Babel. Because it plays such a central role in Death by Design, artist Dave Taylor did a lot of research before finalizing its design. His choices are inspired. The exterior of Wayne Central is drawn from the Boston Avenue Methodist Church in Tusla, Oklahoma, designed by Adah Robinson and Bruce Goff. With a little chiaroscuro, the Art Deco building fits perfectly into the Gothic-deco skyline of Gotham. The interior, however, is pure Penn Station. Designed by McKim, Mead and White in 1910, New York’s Pennsylvania Station was one of the greatest examples of Beaux-Arts Architecture in the United States. It’s destruction in 1963, and the subsequent construction of Madison Square Garden, sparked an re-evaluation of New York’s self-proclaimed “master builder” Robert Moses and acted as the catalyst for preservation movements across the United States, most notably New York’s own Landmarks Preservation Committee.

[left: Wayne Central Station, Gotham; right: Pennsylvania Station, New York]

[left: Wayne Central Station, Gotham; right: Pennsylvania Station, New York]

In a recent interview, Kidd described his experience with Penn Stations current subterranean incarnation:

“…as somebody who takes Amtrak a lot, I’m always in and out of Penn Station and it’s an absolute travesty. Basically — for one of the most active travel hubs on the east coast of the United States – it’s more or less is a fluorescent-lit airless basement below Madison Square Garden, and it’s just horrible. And almost as a cruel joke, when you’re down there, they have these pictures up on the grimy tiled walls of the old Penn Station – this big, glorious space. They’re hanging around on the walls practically mocking you with how beautiful it used to be, as opposed to how shitty it is now”

Kidd’s observation, shared by every single person who has ever been forced to set foot in that rhizomatic dungeon, brings to mind a remark by architecture historian Vincent Scully. In describing the transformation of Penn Station, Scully wrote something like “we used to enter the city like gods, now we scurry in like rats.” In Death by Design, Bruce Wayne hopes to replace his proxy Penn Station with a radical new design by noted European architect Ken Roomhaus –a proxy even even more thinly-veiled than Penn Station– so he can flutter in like a bat, or as the architect says, be “spat out onto the sidewalk.”

[Ken Roomhaus and his design for the new Wayne Central Station]

[Ken Roomhaus and his design for the new Wayne Central Station]

In lieu of his usual bevy of supervillains, Death by Design presents Batman –and Bruce Wayne– with an unusual rogues gallery made up of a beautiful preservationist and an investigative architecture critic (of all the fantasies in Death by Design, “investigative architecture critic” is perhaps the most unbelievable). The cast is rounded out by devious contractors, reclusive architects, and a mysterious new costumed vigilante named Exacto – as in knife. Kidd has described Exacto as “Batman villain as architecture critic,” though that’s not quite right. He’s more of a proactive agent of the building department. Exacto makes his debut by warning dancers on a glass-floored nightclub high above the streets of Gotham: “The stresses on this structure were improperly calculated!” Along with incorporeality and teleportation, Exacto’s superpowers seem to include unlimited access to classified construction documents and forged union contracts. As more and more construction accidents befall Gotham, its citizens are left to wonder: who is the mysterious Exacto? Is he causing these accidents or are his intentions purely to combat faulty construction? Those questions are only two of the many mysteries that drive the plot of Death by Death.

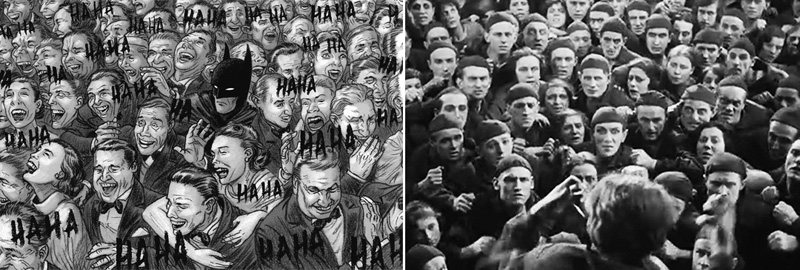

Unfortunately, there are too many mysteries: collapsing cranes, demolished buildings, the disappearance of a famous architect, and, for good measure, an old-fashioned kidnapping. The story’s ambitions are too great, and it fails to fulfill the promises it makes. Chip Kidd is famed as a graphic designer but this is his first foray into writing comics. Though he’s crafted a heroic, convoluted narrative that could have come out of The Fountainhead or Robert Moses era New York, at times his inexperience with the medium shows. The story is beautiful but flawed with a rushed ending and plot threads that seemed to get snipped too short. And while his enthusiasm for architecture is appreciated, Kidd creates an apocryphal architectural jargon that is completely awkward and unnecessary. Roomhaus’s work is alternately described as “Maxi-minimalism” and “Mini-maximalism,” while the clearly Art Deco Wayne Central Station is described as “the single best example of Patri-monumental Modernism in America.” These terms not only takes the story out of a fictional golden age and into a full-on alternate dimension but also undermine the extensive research done by the book’s writer and artist, whose stunning drawings make up for any shortcomings. Taylor took his stylistic cues from Kidd, who as the story’s “art director” gave his artist a mandate that can be summed up on one very specific question: “What if Fritz Lang had a huge budget to make a Batman feature film in the 1930?” Indeed, many set pieces and entire scenes seem in Death by Design seem to be drawn straight from Lang’s Metropolis.

[left: Batman fights through a crowd in Death by Design; right: a scene from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis]

[left: Batman fights through a crowd in Death by Design; right: a scene from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis]

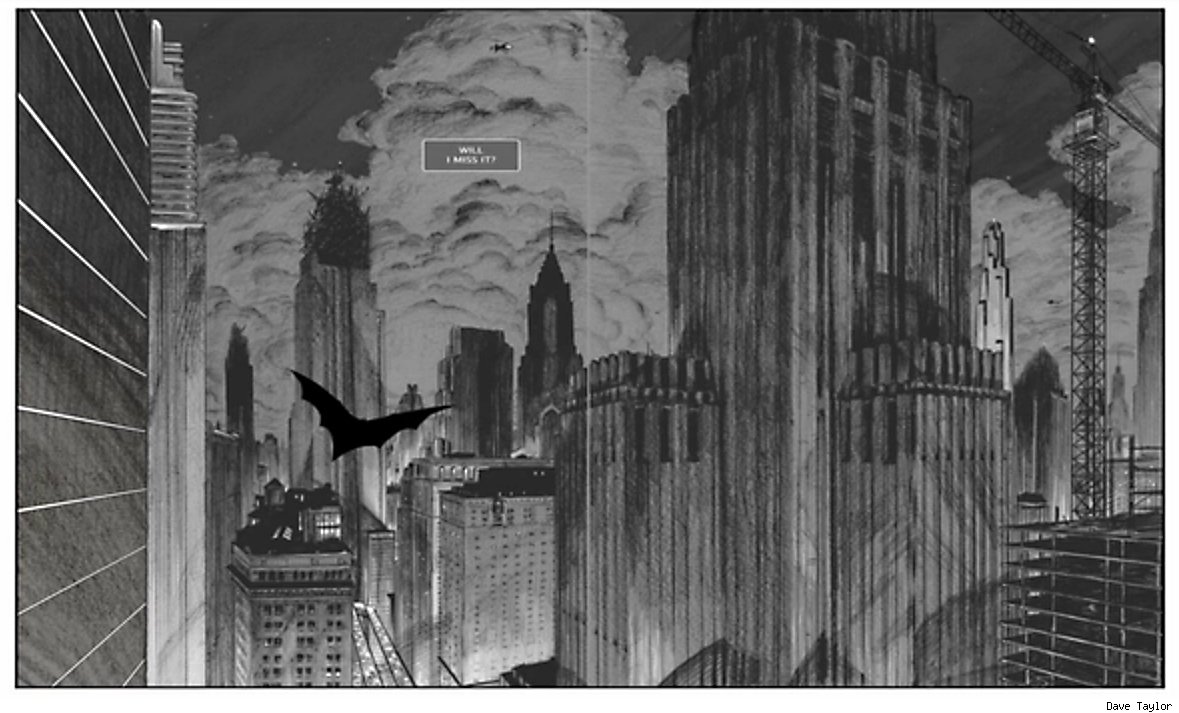

A massive debt is also owed to the work of 1920s-1930s architectural renderer Hugh Ferriss. Ferriss’s renderings were the inspiration for Tim Burton’s vision of Gotham City and subsequently shaped the image of the city in the comics as well. Taylor’s pencils evoke Ferriss’s renderings without being derivative. The black and white monolithic Art Deco buildings of Gotham place the story firmly in the era of Ferriss’s iconic and much sought-after renderings. It also reveals, in surprisingly detail, the difficulties of getting such massive skyscraper builts in a city like Gotham or New York. To make sure this process was described realistically –as realistically as possible in a story involving teleporting masked vigilantes– Kidd consulted with friend and architect Bart Voorsanger. Artist Dave Taylor notes:

“The book contains some of the truth behind how a city is built, literally. The corruption, and misplacement of power rings true to the point of making this book a timely record. But what this book does above all is show how easy it can be to bring that corruption and power down, all you need is one hero!”

Even with its the overwrought plot, Death by Design is an entertaining paean to Batman and to architecture that wears its heart firmly on its cape. It really is exciting to see architecture presented as the driving force of a comic book plot instead of just background scenery. The Architecture of Gotham has always been integral to the Batman myth (As I’ve previously noted), and Kidd and Taylor articulate that connection in an exciting and innovative way. Buildings are represented heroically and heroes are revealed to be mere men, struggling against the very city they created.

[Batman soars above Gotham City in Batman: Death by Design]

[Batman soars above Gotham City in Batman: Death by Design]

Death by Design also alludes to larger questions about architecture, important questions. What makes a monument? How can we preserve tradition while still embracing innovation? What is the value of an architect’s legacy? To some, it may seem silly to look toward comics for these answers, but Batman has been around since 1939 and his history has been not only preserved, but enriched and updated for a modern audience – even when it takes the form of a retro-pulp story. If Batman has taught us anything, it’s that the past invariably shapes who we are. It cannot and should not be forgotten or ignored, for by looking to the past we can certainly find timeless lessons that shape the people we are and the cities in which we live. But we cannot dwell on the past completely; we cannot let it consume us. In order to truly resonate with a contemporary audience, an expression of tradition must reflect current social and technological realities. It’s like I’ve always said: as goes Batman, so goes architecture.

[portions of this post originally appeared on Life Without Buildings]